Why Version Control Matters

Introduction to Git Basics

VCS means version control system, and lets a developers work in the same code base together without stepping on each others’ codes.

Life without Version Control

Cowboy coders – coders who don’t follow best practices.

If you write a feature, decide you don’t want it and delete it, but then then decide you want it later, it helps to have a version of each time you saved on hand, with a description so you can pull up what you need. Even then, if you were working on this with another person, it’d be hard to compare your code and changes.

How Version Control Works

It’s called a VCS because it let’s you control all the versions of what you’re working on. Revision Control or Source Control mean the same thing. A repository is a collection of all the different versions of a project. It includes the the order the changes occurred in, a description of each change, and who was responsible for each change. Each project will have its own.

It wouldn’t make sense to treat unfinished work as a version. The VCS doesn’t know when a change has occurred, you have to tell it, which is called committing. Versions are often referred to as commits. Doing this manually is messy, and the VCS tries to hide this from you by storing the files in special hidden folders.

To explore your changes, it will give you a set of tools to explore your revision history. Like being able to view and filter the list of commits, or what version is displaying. They also allow you to share your repositories with other to work on things together.

Why Git?

Inventor of Linux made this as well. Linux is a huge project, and Git was designed to help with collaboration on that. Git is a distributed VCS. Some VCS are centralized, meaning that the repository sits on one server. You can’t access it without a network connection, and it can be easily lost if the server is destroyed. For distributed ones, there is no central repository, everyone who works on a project has their own.

Originally Git was going to be a set of tools and commands (plumbing) for you to build your own VCS (porcelain), but eventually it evolved into one itself. It still has the internal tools and commands though, which give you a lot of power.

Github is the most popular site for sharing your repositories.

Getting Started with Git

Working with Git Repositories

Creating and working with repositories is a simple process in git. First, we’ll check to see if git is installed using the –version flag.

To create a repository, type git, then init, then the name you want to give it. This will give you a success message saying where it’s been created.

Looking inside it, there’s nothing there. It’s not just an empty directory though, remember it puts a lot of stuff in hidden files and folders. With -a we can see those, including the .git directory, which will contain all the info on our project eventually.

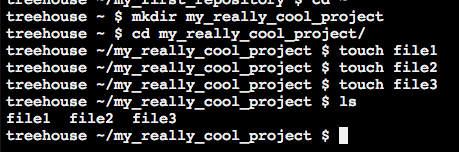

Let’s say you made a directory with a bunch of files before making the repository.

Just run git init without giving it a project name. Since you didn’t give it a folder name, it will assume you want a new repository for this folder.

Note that the name of the repository is not essential, so long as the .git folder exists within it.

The .git is the only thing that matters, you could actually delete everything else in that folder and still restore your work. To remove the repository, you’d just delete the .git folder.

Committing Changes

We’ll start by making a repository, going into it, then creating a read me file with nano.

We’ll then add some text, and save it. We’ve now created a new file in our repository.

Before we can commit it, we need to add the file to the repository, letting git know the file is important and that its changes should be tracked there. We do this with the git add command. You have to do this manually as there may be some files you don’t want to add or track.

Next we use the git commit command to commit our changes.

Lines starting with # are comments. It tells us some info like the committer, what branch we’re on, and what we changed, in this case, we added a new file README. We’ll add our description at the top, which should be short and meaningful. Save and exit nano.

You get a success message, and info on your name and email. It’s important to know who did what, in case someone needs to get in touch with you. If it’s not listed, it will try to guess based off your username. To change them, we’ll use the —global flag to let them know we want to change this for all of our repositories.

Now that the file is in the repository, let’s go back and edit it a bit.

So we’ve made a change, should we commit it? Good rule of thumb: if there is a good commit message you should use, then you should. You should commit when there is good reason to, the more often you do, the better your version history will be. We’ll use git commit again, this time with the -a flag, for all, which means to commit all the changes it can find. The -m stands for message, and let’s us add the commit message from the command line without having to go into nano.

It’s better to err on committing more often than not.

The Staging Area

The staging area let’s you control what you want to include in the commit. The git status command shows the current version control status of the project. It tells us what branch we’re on, and that there aren’t any changes to commit, as nothing has changed.

Right now we just have the README, let’s add some more files and rerun git status.

It tells us we have three untracked files, and you can see it tells us we need to add them to the repository before they can be tracked.

File1 has been moved to the “changes to be committed” section, which is known as the staging area. If we add the other two files to the repository, they’ll be there as well.

We can then add them like before.

Now, we’re back to the original status of nothing to commit.

Let’s change file1 and 2 with nano. You can see they’re listed under “changes not staged for commit”. Git knows the files are in the repository and it needs to track them, but they’re not in the staging area.

Let’s just add and commit file1, using the git add and commit commands.

If we rerun git status, we can see file2 is still there. We can add it the same way.

Looking Back on what We’ve Done

How do we review the commits we’ve saved to the repository? The git log command shows us a log of all the commits, starting with the most recent. Each entry includes a unique commit identifier, aka a hash. You can see the author and date of the commit as well, and the commit message.

To see the details of a specific commit, use the git checkout command, which uses the git identifier. It doesn’t need the whole thing, just enough so it knows which one you’re referring to, usually the first 5-6 characters.

The detached head state warning just lets you know that you’ve pulled up an older version of your code, and if you try to make any changes things could get weird.

If you ls, things will look like they did before, but if you cat file1 and file2 you can see they’re empty here.

So how do you get back to where we were before, to the present state? Use git checkout, then master.

The get diff command lets you see what’s changed between two versions of a project. It takes two arguments, the id of the first commit, and the id of the second.

You can see the only difference is that “This is file2” was added to file2.

Branches

Branches are like alternate realities for your project, they let you pursue different course courses of action for your project in parallel.

Beginning to Branch

Master is the default branch in any git repository, and is usually the canonical version of your project, meaning the one that’s deployed in production. This is optional of course, but is the typical convention.

To make a new branch, use the git branch command, and give it a name, which should be short and meaningful.

We made it, but we’re still on the master branch. To switch, use the git checkout command again, which makes sense because a branch is just another version of our code. By default it will take you to the latest commit for that branch, aka the head commit.

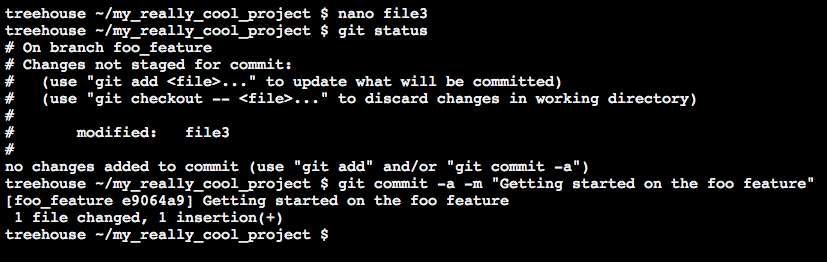

Let’s change and commit file3 here.

We can see this commit is at the top of our git log now for this branch.

If we were to switch back to the master branch with git checkout master, then check its git log, this commit would not be there, only in its branch.

You can create a new branch and switch to it at the same time by adding the -b flag to the git checkout command. Now, while in the foo_feature branch, let’s do this. Since we created it off that branch, and not master, the file3 commit is here as well. When you make a branch, it copies whatever branch you were on at that time.

Managing Branches

The git branch command will list all the branches, with the one you’re in at the moment starred.

To delete a branch, use the -D option with the git branch command, followed by the name of the branch. NOTE: You can’t delete a branch you’re currently in.